In a number of projects and proposals, architects and urban planners are working with water instead of against it

In 2003, Jacques Lacour and his brother, Ovide, built a fishing lodge on a sliver-shaped lake called Old River that was once part of the Mississippi, near Batchelor, Louisiana. Leveraging local knowledge and techniques that had been developed over decades, they hit on an architectural concept that is becoming in vogue as climate change drives flooding events around the world. They made their business, called Old River Landing, amphibious.

Batchelor is an agricultural community, specializing in sugar cane. But Old River hosts anglers, who come up from Baton Rouge or Lafayette and stay in private or public lodges called camps. Starting in the late 1970s, some homeowners started making their camps amphibious. Now, when the lake rises, so do the camps.

“We need to acknowledge that the water is eventually going to do what the water wants to do, and shift our approach, as human populations living on the Earth, from one of trying to dominate nature to one that acknowledges the power of nature and works in synchrony with that,” says English. “We’ve already set ourselves down this path of dams and levees and water control systems, and it’s really hard to turn back. But we don’t need to keep replicating that. We don’t need to make the situation worse. It’s time to step back from the approach of control and fortification.”

When Hurricane Katrina flooded 80 percent of New Orleans, displacing a million people and causing more than $100 billion in damages, English was working at the Louisiana State University Hurricane Center on the aerodynamic behavior of windborne debris. The disaster, especially the failure of the levees, made her realize that flooding could do far worse damage than wind ever could. More recent hurricanes, too, have had their effects exacerbated by the design of the cities they have hit. While Hurricane Irma caused less-than-expected flooding in Florida, Hurricane Harvey was catastrophic due to the rainfall it dumped on Houston. City planners have attributed much of the flooding there to the prevalence of blacktop and concrete, which keeps water atop the landscape rather than letting it settle in.

To protect homes from flooding, FEMA encourages static elevation (raised houses) and won’t certify amphibious homes for the National Flood Insurance Program, meaning residents often have to climb stairs and deal with the visual impact of elevated houses. “The response of the Federal Emergency Management Agency was, in my opinion, entirely insensitive to the cultural context of New Orleans in particular, and South Louisiana in general,” says English. The permanent, static elevation was disruptive to the aesthetic feel of the historic neighborhoods there. A student told her about Old River Landing, and she began to discover amphibious homes in other parts of the world.

But there are more ways to work with water than mitigating flood impacts. Architects and urban planners are reevaluating all the ways cities interact with water, from transport to recreation to energy to drinking water, and their ideas have the potential to fundamentally alter cities the way the car did in the 20th century.

“Cities that today start to embrace water and take advantage of the skills of water, will be the cities that have a better performance economically and socially and politically in 20 to 30 years,” says Koen Olthuis, founder of Waterstudio, a Dutch firm that has found designing around water to be more than a niche market. “When situations change—and that’s happening now, the environment is changing, the climate is changing—cities have to react. You have to change the skills and the performance of the city to give a reaction to this situation, and the reaction should be not fighting it, it should be living with it.”

Olthuis calls this idea the Blue City, and sees a coming progression, from green cities (low impact) to smart cities (connected and responsive), to blue cities, which use water to be both of the previous. An ideal city, he says, would accomplish this by using water to achieve three types of goals—to reduce energy needs, to generate energy, and to store energy.

Waterstudio is working with Oddysea Development to showcase these strategies and more in a multipurpose entertainment resort on a one-square-kilometer man-made island in Bahrain. Called Arabian Oddysea, the project is scheduled to break ground in 2019 and be completed in 2023, according to chairperson Dara Young. The estimated $6 to 7 billion project will include shops, hotels and restaurants, as well as an aquatic sanctuary, a man-made mountain and an Arabian horse track. But along with—and integrated into—the entertainment, Arabian Oddysea will incorporate water in ways designed to improve energy efficiency.

“Integrating ways to sustain our needs by channeling energy allows us to lead by example. Bahrain was first to discover oil, so we’d like Bahrain to be the first in the region to introduce architectural hydropower,” says Young. “Over the next five years, the gulf countries are expected to need to generate 40 percent more electricity than they are now … and it’s important to stay ahead of the curve and come up with alternative solutions.”

To do that, Arabian Oddysea is incorporating several Waterstudio-designed elements that each use water in a different way. One is a sea wall, but it’s not designed like normal sea walls, which tend to be big chunks of concrete that waves smash up against and eventually demolish. Called Parthenon, the seawall is made of columns of turbines hanging underneath like the pillars of its namesake. As waves flow in and out, they drive the turbines, which generate enough energy for about 50 houses, but also reduce the action of the water so that behind the wall, the water remains calm.

Another feature is an array of floating solar panels that lie just beneath the surface of the ocean. In hot climates, exposed directly to sunlight, solar panels quickly exceed the optimal operating temperature. But when water is allowed to flow over them, they absorb sunlight at a balmy 80 degrees. There will be floating solar panels just offshore of the man-made island in Bahrain. (Waterstudio)

All that energy needs to be stored, somehow, and batteries are expensive. Arabian Oddysea plans to use it to pump water into tanks housed high in tall buildings called blue batteries, and then let it flow back down to run turbines once the sun is down. According to Young, 25 percent of off-peak energy needs will be housed in the blue batteries.

Another element of the Oddysea is a system of water-filled tubes running through walls and floors in buildings, squares and city streets. The water pumped through helps cool the city, reducing load on air conditioning.

Even the entertainment will incorporate water, says Young. The horse track will be suspended over water features. The water drained from the blue batteries will tumble down 200-foot “hydrokinetic waterfalls” that house the turbines.

Othuis’ vision doesn’t stop with the Bahrain project. He speaks of floating museums or stadiums that could be shared between cities across bodies of water, or even whole cities that move, or expand and contract, with the seasons, increasing density to maintain warmth and opening like a flower in the summer. A true blue city would incorporate these designs and more to treat water like a tool, rather than a threat.

“There are many things that won’t work, [and that] will maybe always be part of a futuristic scope or vision,” Othuis says. “But you see that some of these ideas in the end will be part of the next generation of cities.”

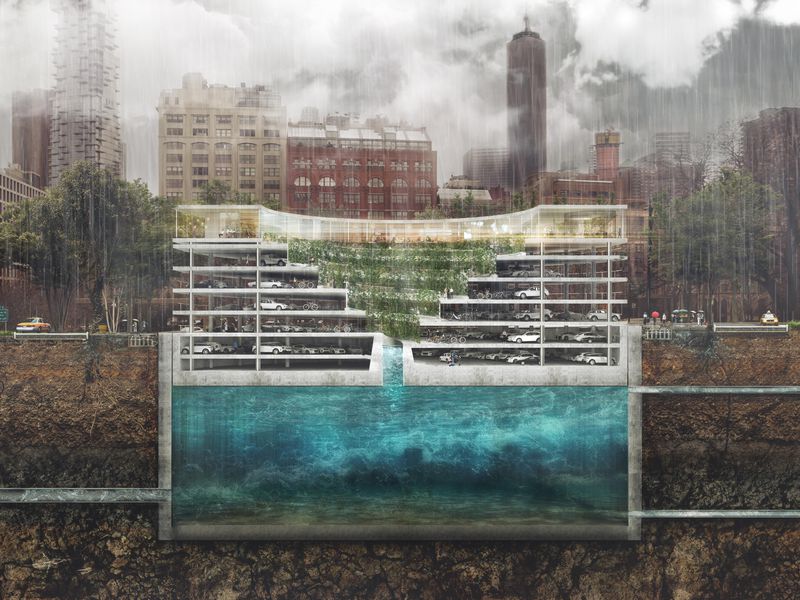

Oddysea is somewhat unique in its scope, its price tag, and its virgin landscape. But there are many other ongoing projects and proposals that tap specific innovations to address smaller aspects of water management. A permeable concrete from a UK company called Tarmac can absorb 600 liters of water per minute per square meter. A Danish architecture firm has designed a parking garage that sits atop a water reservoir and rises atop floodwaters as they drain into the reservoir. Dikes in The Netherlands now house sensors that can give managers advance notice of overloading, allowing them to evacuate or divert water when one part is getting too much stress. In San Francisco, new developments over 250,000 square feet are required to install and operate grey water recycling systems.

With the Bahrain project, Waterstudio has the benefit of working on a new development, where designs aren’t constrained by what’s there already. Much of our waterways, however, already share coastlines with buildings or other structures that would need to be adapted or discarded. That is what Baca Architects and H+N+S Landscape Architects, are doing on the Waal River in the Netherlands. A 1995 flood led to the development of that nation’s Room for the River program, which seeks to accommodate the changes to the rivers there, and the Waal River is a flagship project for the program.

At a bend in the river, near the German-Holland border, the town of Lent was at risk. A low-lying area just inside a higher peninsula, sort of a short cut for the river flow, was liable to flood. Over the last decade and a half, the city relocated around 50 dwellings and farmsteads, and H+N+S dug out a channel, turning the peninsula into a seasonal island. Now, the river would have space to flow, alleviating flooding not just in Lent, but downstream as well.

“This marks a fundamental shift in thinking, to date, in Holland, Germany, the UK, who have consistently built … with the presumption in terms of policy is we hold water out,” says Richard Coutts, director of Baca Architects.

If the Veur-Lent project goes well, it could serve as a model for other cities and riverways. But there are still regulatory hurdles to building in a style that’s unfamiliar. FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program denies coverage to floating homes, while extending it to houses that are on the ground and likely to flood. Amphibious buildings, like Old River Landing, are ineligible at any price. Just like many of their neighbors, the Lacours built it anyway.

“It’s a way of life that we’re all accustomed to,” says Lacour. “Growing up on the river, there’s nothing like firsthand experience of seeing what water can do, and if you try to, you may find a solution for those situations. I think we’ve adapted to the changing conditions of our rivers.”

No comment yet, add your voice below!